Designing CLI documentation from the ground up

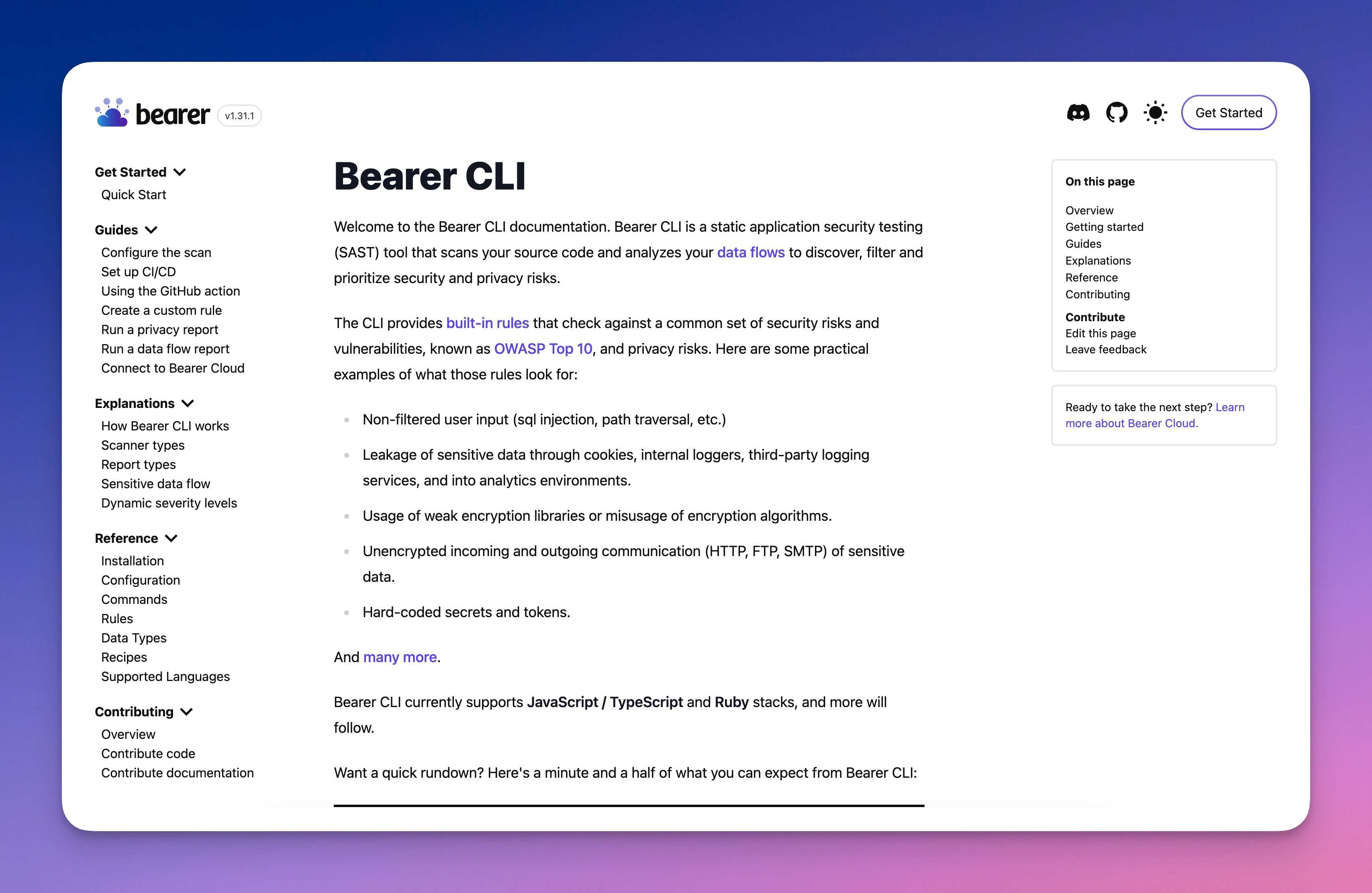

At Bearer, one of my final projects as a technical content manager with the company involved the documentation for their open source project, Bearer CLI. I acted as the primary technical writer, technical editor, and documentation architect.

Bearer CLI is a security and privacy scanning tool that analyzes a codebase and returns a report of potential vulnerabilities, as well as guidance to help engineers resolve the problem.

Working alongside the engineering and product teams, I developed and managed the roll-out of the beta, launch, and first few release months of the project’s lifespan.

This case study covers the architectural and content decisions. Future articles will cover implementation details, like building a documentation solution with 11ty.

Goals

The users of CLI tools expect a base level of documentation to exist in the tool itself, but outside of man pages and help text there is a lot of value in web documentation.

As this was a brand new product aimed at open-source, we went in with a few core goals:

- Highlight the 90% path.

- Rely on the CLI source files whenever possible.

- Enable contributors to easily add to or update pages.

Organizational decisions

I made the decision early on to loosely base the structural organization on the diátaxis framework . Diátaxis bills itself as a grand unified theory of documentation. Beyond some core principles around user needs and pedagogy, the framework breaks down documentation pages into four categories:

- Tutorials

- How-to guides

- Reference

- Explanation

For Bearer CLI, we muddy the tutorial/how-to categories a bit into a single “Guides” section. In part to reduce friction for contributors and others on the team, but also because the tool is small in task surface. There’s a more detailed explanation here, but that’s better suited for a dedicated article.

This leaves the docs with a quickstart, three primary sections, and an additional area dedicated to contributions. The information architecture, as shown in the sidebar looks a bit like this:

- Guides

- Explanations

- Reference

The quickstart guide fits the diátaxis tutorial grouping, but we surface it at the top level as a low barrier way to jump in.

Guides

The guides are the core of the learning experience. Once a user finishes the quickstart, they can perform the primary path of the application. Beyond that, we wanted an expanding list of “features” for them to explore. Guides offer learning paths beyond the core experience.

Explanations

Even good documentation frequently omits the “why.” Explanations provide a way to explain things like rationale, inner workings, and priorities for the way an application works. They also act as reference pieces for the rest of the docs. Instead of interrupting a guide or reference document with lengthy descriptions, you can offload the bulk of the explanation to individual explainer docs.

For Bearer, we used this to describe underlying algorithms, make the case for why opinionated decisions were made, and explain core functionality.

While it is tempting to spread explanation into reference documentation, it’s valuable to separate the two and keep reference pages scannable.

Reference

Far too many teams deliver reference docs as the only documentation. This is a mistake, but it doesn’t mean that reference materials aren’t valuable. We generate the majority of reference docs in Bearer CLI directly from source. This helps keep the application as the source of truth and prevents divergence between the docs and application.

It also encouraged the team to put more effort into the in-app documentation. In most instances, in-app help text included a link to the web docs for additional clarification.

Contributing

A project goal from the start was to encourage community contributions. The team moved all project management tasks and discussions into the GitHub repository, and we developed specific contribution guidelines for all levels of contributions. They broke down into these categories:

- Code: Anything directly affecting the core CLI app. For Bearer CLI, this mostly meant detection and classification code, but could also be general improvements to the CLI code itself. This section included specifics on building and running the CLI from source.

- Docs: Documentation-level contributions normally involved the docs site, but due to the way we generate remediation pages these often involved editing rule configurations. Documentation contributors are encouraged to use GitHub’s built-in editor interface for small additions, but we also included instructions on running and building the docs on their own.

- Recipes: Recipes connect data detections to external resources. These weren’t an initial launch concern, but we received enough user feedback to justify the dedicated page.

Content

The content approach wasn’t itself unique. I took the traditional technical writing angle of simple, direct instructional material. Because the tool was relatively new for a developer audience, I also highlighted adjacent use cases and potential areas where tasks may be valuable.

Documentation like this acts as an exploration guide as much as it does a learning aid. It teaches how to do something, but also shows what can be done.

Connecting CLI to docs

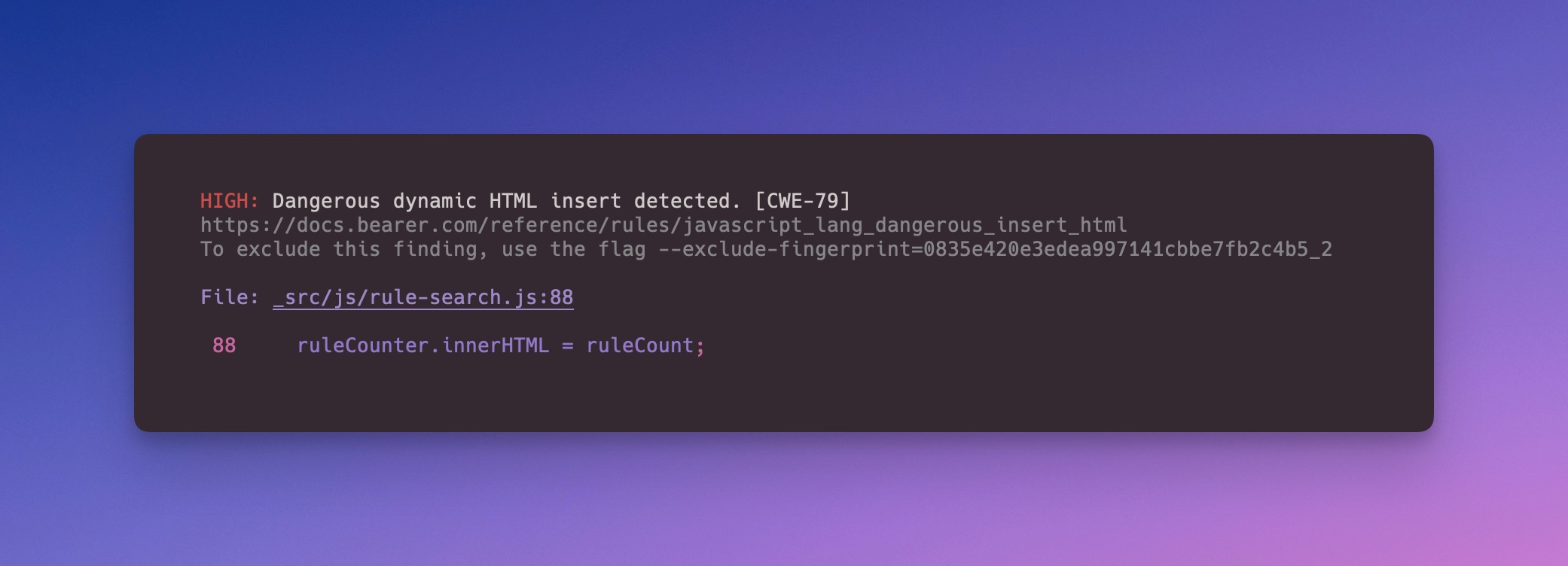

It was important from the very beginning to make documentation a priority. One of our biggest commitments to this best demonstrated by the deep documentation links directly in the CLI output.

For the less common detection warnings, the addition of a documentation link was incredibly valuable. It enabled us to remove the need for developers to google the error or hunt for remediation steps. Instead, they could simply click through to the docs.

Docs as code, and code as docs

Another big decision involved managing the individual rules for the scanner. Each rule tells the scanner what to look for. We combined metadata, remediation steps, and documentation output into shared configuration files—YAML format—to allow the CLI and our static site generator to consume and interpret the information.

Each rule YAML file could then drive:

- Documentation reference pages.

- CLI report output.

- GitHub pull request feedback.

- Future SaaS offerings and cloud components.

It also meant that the rules never had a “source of truth” problem. The only hurdle in that area came with rules that shared very similar concerns, such as technically different concepts that were abstractly similar. Think different languages handling the same problem area.

Here’s a snippet of a rule, highlighting the shared metadata:

# ...

trigger:

match_on: stored_data_types

severity: warning

metadata:

description: "Missing application-level encryption of sensitive data detected."

remediation_message: |

## Description

Application-level encryption greatly reduces the risk of a data breach or data leak by making data unreadable. This rule checks if sensitive data types found in records are encrypted.

## Remediations

Whenever storing sensitive data to a datastore, make sure to encrypt the entire record, or the field itself.

## Resources

- [Ruby on Rails Active Record encryption](https://guides.rubyonrails.org/active_record_encryption.html)

cwe_id:

- 312

id: ruby_rails_default_encryption

documentation_url: https://docs.bearer.com/reference/rules/ruby_rails_default_encryption

Takeaways and revisions

The project was an interesting challenge. We had a small team, myself as the sole writer, and heavy marketing influence. This meant balancing instructional and documentation goals with business needs. There are some areas where business goals shaped the ideal documentation structure, but overall the user experience was still maintained.

If I were approaching this today, I’d also incorporate an outward-facing style guide as part of the contributing guide. This paired with tooling like Vale for linting and style checks would improve the long-term quality and consistency.

Interested in seeing the docs mentioned in this study first-hand? They’re still available at docs.bearer.com. View the source on GitHub, and filter back to the early pre-1.0 and 1.0 versions to see the implementation discussed here.